The "Aryan" Story vs. True Aryan History.

I. The "Aryan" Story.

[This is an attempt to encapsulate within one reasonably short article the entire question of the "Aryan" problem. The subject has been dealt with in extremely great detail in my three books and in my numerous articles and blogs, but few people will have the interest or patience to go through all the details. This article attempts to place the subject in short in one place. Of course, being a technical subject, it will not be lacking in tediousness, but (and especially in the face of the growing propaganda about so-called "Aryan-Dravidian conflicts" as represented, I am told, by the new film "Aarambh") I feel the whole subject should be understood in brief by all Indians].

1. There is no oral or written tradition, and never was any, anywhere in any part of India about any people called "Aryans" who came into India as invaders or immigrants and brought the Vedic Sanskrit language and Vedic religion and culture into India. The concept of these "Aryans" was invented in the 18th-19th centuries by European scholars. Therefore any history or stories written today, showing these "Aryans" as a historical people in ancient India and depicting events, incidents and stories in which these people figure as "Aryans" contrasted with any other people who figure as "non-Aryans", are purely imaginary and fictional stories with no basis in any fact, and born only out of the colonialist imaginations of European scholars of the 18th-19th centuries and perpetuated by dirty hate-inspired modern Indian politics.

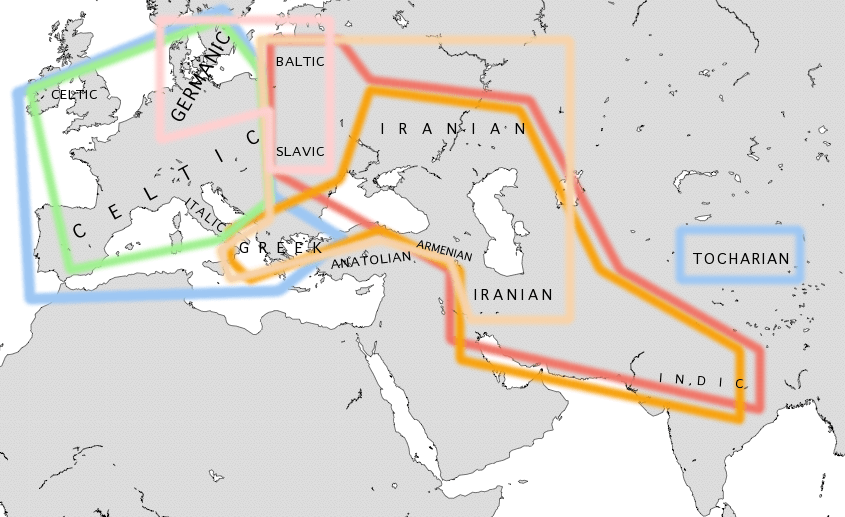

2. When the European colonialists came to India post the European Medieval Period (which ended in the 15th century), the scholars among them were impressed by India's Sanskrit language, grammar and literature. What stunned them the most of all was that the Sanskrit language was clearly related to their European Classical languages Greek and Latin. Further research showed there was indeed a linguistic relationship between Sanskrit, all the European languages (except a handful of languages in eastern Europe like Finnish, Hungarian and Estonian, and the Basque language of northern Spain) as well as the languages of Iran, parts of Central Asia, and most of northern India. All these languages were classified as belonging to the "Aryan" family of languages (based on the fact that the poets of the two oldest texts in these languages, the Indian Rigveda and the Iranian Avesta, referred to themselves as ārya/airya). Today, this is called the Indo-European family of languages. The linguistic facts are:

a. All these languages (constituting 12 branches: Hittite, Tocharian, Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Albanian, Greek, Armenian, Iranian and Indo-Aryan) are related to each other and belong to one language family, distinct from other neighbouring languages.

b. They are all descended from a common ancestral language, which has been artificially and approximately reconstructed by the linguists and has been named "Proto-Indo-European".

c. This Proto-Indo-European language was originally spoken in one particular area, and it broke up into distinct dialects which spread out to different areas and became the 12 historical branches of Indo-European languages. This particular area was the Original Homeland of the Indo-European languages.

d. The evidence of linguistics shows that the different dialects (which later became distinct branches of Indo-European languages) were in contact with each other in an area of mutual influence in and around the Original Homeland (wherever this Homeland was located) till around 3000 BCE, and only started to separate and get cut off from each other at around that time.

3. The above are the linguistic facts. The above linguistic facts themselves do not, in any way, indicate the location of the Original Homeland. But linguists arrived at a consensus that this Homeland was in South Russia. This automatically led to the conclusion that all Indo-European languages spoken outside South Russia must be the results of migrations of Indo-European speakers from South Russia. This is the only basis for assuming that the speakers of the Vedic language came into India from outside: there is no internal evidence of any kind within India to support such a theory. The date of around 1500 BCE for their assumed invasion/immigration is based on a series of conjectures about the time and routes they "must have" taken for their assumed journey setting out from South Russia around 3000 BCE, in order to reach India well before the post-Vedic Buddhist period from 600 BCE onwards.

4. The linguistic facts, of course, have to be explained, and the three fields of study which can determine the location of the Original Homeland are Archaeology, Textual Analysis (of the Rigveda) and Linguistics.

5. Of these, Archaeology completely disproves the idea of any Indo-European movement into India around 1500 BCE:

a. To begin with, absolutely no archaeological evidence has been found of the Proto-Indo-European language spoken in Russia before 3000 BCE, or of the Indo-Iranian speakers moving from South Russia to Central Asia between 3000-2000 BCE, or of the Indo-Aryan speakers moving from Central Asia to the Punjab around 1500 BCE, or even of the Vedic Indo-Aryans moving from the Punjab into the rest of northern India after 1000 BCE. Even Michael Witzel, who is spearheading the AIT battalions, admits that archaeology offers no proof of the AIT: "None of the archaeologically identified post-Harappan cultures so far found, from Cemetery H, Sarai Kala III, the early Gandhara and Gomal Grave Cultures, does make a good fit for the culture of the speakers of Vedic […] At the present moment, we can only state that linguistic and textual studies confirm the presence of an outside, Indo-Aryan speaking element, whose language and spiritual culture has definitely been introduced, along with the horse and the spoked wheel chariot, via the BMAC area into northwestern South Asia. However, much of present-day Archaeology denies that. To put it in the words of Shaffer (1999:245) ‘A diffusion or migration of a culturally complex ‘Indo-Aryan’ people into South Asia is not described by the archaeological record’ […] [But] the importation of their spiritual and material culture must be explained. So far, clear archaeological evidence has just not been found" (WITZEL 2000a:§15).

b. In fact, archaeologists are almost unanimous on the point that there is absolutely no archaeological evidence for any change in the ethnic composition and the material culture in the Harappan areas between "the 5th/4th and […] the 1st millennium B.C.", and that there was "indigenous development of South Asian civilization from the Neolithic onward"; and further that any change which took place before "the 5th/4th […] millennium B.C." and after "the 1st millennium B.C." is "too early and too late to have any connection with ‘Aryans’".

c. The archaeological consensus against the AIT is so strong that in an academic volume of papers devoted to the subject by western academicians, George Erdosy, in his preface to the volume, stresses that this is a subject of dispute between linguists and archaeologists, and that the idea of an Aryan invasion of India in the second millennium BCE "has recently been challenged by archaeologists, who ― along with linguists ― are best qualified to evaluate its validity. Lack of convincing material (or osteological) traces left behind by the incoming Indo-Aryan speakers, the possibility of explaining cultural change without reference to external factors and ― above all ― an altered world-view (Shaffer 1984) have all contributed to a questioning of assumptions long taken for granted and buttressed by the accumulated weight of two centuries of scholarship" (ERDOSY 1995:x). Of the papers presented by archaeologists in the volume (being papers presented at a conference on Archaeological and Linguistic approaches to Ethnicity in Ancient South Asia, held in Toronto from 4-6/10/1991), the paper by K.A.R. Kennedy concludes that "while discontinuities in physical types have certainly been found in South Asia, they are dated to the 5th/4th, and to the 1stmillennium B.C. respectively, too early and too late to have any connection with ‘Aryans’" (ERDOSY 1995:xii); the paper by J. Shaffer and D. Lichtenstein stresses on "the indigenous development of South Asian civilization from the Neolithic onward" (ERDOSY 1995:xiii); and the paper by J.M. Kenoyer stresses that "the cultural history of South Asia in the 2ndmillennium B.C. may be explained without reference to external agents" (ERDOSY 1995:xiv). Erdosy points out that the perspective offered by archaeology, "that of material culture […] is in direct conflict with the findings of the other discipline claiming a key to the solution of the ‘Aryan Problem’, linguistics" (ERDOSY 1995:xi).

On the other hand, there is conclusive archaeological evidence for the arrival of the European branches (the Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic branches) into Europe from the east, for the arrival of the Hittites (the Anatolian branch) into Turkey (Anatolia) from the northeast, for the arrival of the Greeks and Albanians (the Greek and Albanian branches) into Greece from the east (across the Aegean Sea), and for the arrival of the Tocharians (the Tocharian branch) into the Qinjiang province of China from Central Asia to its south. [The arrival of the Iranian branch into Iran from the east is recorded in Babylonian texts. The Armenian language (the Armenianbranch) is also clearly an intruder into Armenia, as evident from the evidence of the place names in Armenia]. It is only the theoretically postulated arrival of the Indo-Aryan branch (as represented by its oldest form, Vedic) into northwestern India from further northwest which isabsolutely unsupported by any archaeological evidence.

5. Over 200 years of Textual Analysis of the Rigveda has also failed to provide one single piece of evidence for the AIT:

a. For example, George Erdosy, the editor of the volume referred to above, although a supporter of the AIT, writes: "we reiterate that there is no indication in the Rigveda of the Arya’s memory of any ancestral home, and by extension, of migrations. Given the pains taken to create a distinct identity for themselves, it would be surprising if the Aryas neglected such an obvious emotive bond in reinforcing their group cohesion". He tries to explain it away as follows: "Thus their silence on the subject of migrations is taken here to indicate that by the time of composition of the Rigveda, any memory of migrations, should they have taken place at all, had been erased from their consciousness" (ERDOSY 1989:40-41). The most valiant efforts of two centuries of western Indologists have failed to find a single reference in the Rigveda to any foreign homeland (or area); to any immigration from outside of the Vedic people; to any sense of "newness" felt by the Vedic Aryans to their Vedic territory; or to any person, tribe or entity whose name can be shown to be linguistically Dravidian, Austric, Burushaski, Sino-Tibetan, Sumerian, Semitic, or any other kind of specific "non-Indo-European" (let alone to those persons, tribes or entities being "indigenous" inhabitants as opposed to the Vedic people themselves, or to any conflicts with them, or to any past or contemporary invasion of their territory). The Indologists can only plead subjectively for faith in their AIT: "the IAs, as described in the RV, represent something definitely new in the subcontinent […] The obvious conclusion should be that these new elements somehow came from the outside" (WITZEL 2005:343)". Note the pathetically desperate plea in the "somehow", which Witzel places in italics.

b. In fact, an analysis of the data in the Rigveda (which the Indologists claim was composed after 1500 BCE), in comparison with the data in the Iranian Avesta and the data in scientifically dated West Asian manuscripts and inscriptions pertaining to the Mitanni people (a group ofIndo-Aryan speakers who established the Mitanni kingdom in Iraq and Syria around 1500 BCE, but are known to have been present in West Asia well before 1750 BCE), shows:

i) The common data is found in 425 of the 686 New Hymns and 3692 of the 7311 verses in theNew Books of the Rigveda (5,1,8,9,10) as well as in all later (post-Rigvedic) texts, but is not found in a single one of the 280 Old Hymns and 2351 verses in the Old Books of the Rigveda (6,3,7,4,2).

ii) This shows that the Mitanni Indo-Aryans in West Asia, the Avestan Iranians in Afghanistan, and the Vedic Indo-Aryans in India separated from each other during the period of composition of the New Books of the Rigveda, and after the period of composition of the Old Books.

iii) The geographical area of the New Books of the Rigveda extends from southern and eastern Afghanistan in the west to westernmost Uttar Pradesh and Haryana in the east. This, therefore, is the area from which the Mitanni Indo-Aryans migrated to West Asia: the fact that they entered West Asia from outside, and from the east, is not disputed by anyone.

iv) The fact that the linguistic ancestors of the Mitanni Indo-Aryans are already found in West Asia by 1750 BCE shows that they must have left the geographical area of the New Books of the Rigveda at the very least, and by a very conservative estimate, by 2000 BCE.

v) The development of this common culture of the New Books of the Rigveda, which the Mitanni Indo-Aryans took with them to West Asia around 2000 BCE, must therefore be much older, at least by a few hundred years: i.e. this culture must be at least datable to 2400 BCE.

vi) The totally distinct culture of the Old Books of the Rigveda must precede 2400 BCE by another few hundred years at least: i.e. it must go well into the early parts of the first half of the third millennium BCE.

vii) During this period, i.e. during the early parts of the first half of the third millennium BCE, the geography of the Old Books of the Rigveda is originally restricted to the eastern parts of the geography of the Rigveda as a whole: to Haryana and westernmost Uttar Pradesh. TheseOld Books show that the Vedic Indo-Aryans were residents of Haryana and westernmost Uttar Pradesh and were not familiar with the areas, rivers, mountains, lakes and animals further west, most of which appear only in the New Books. They also give in great detail theconcrete historical events which led to the expansion of the Vedic Indo-Aryans westwards from Haryana, across the rivers of the Punjab to the borders of southern and eastern Afghanistan.

viii) Further, during this period, i.e. even as early as during the early parts of the first half of the third millennium BCE, as the Vedic Indo-Aryans expanded from east to west across the Punjab, the whole area is a purely Indo-European area, with not a single reference to any linguistically non-Indo-European person, tribe or entity, with even the local rivers having purely Indo-European names. [This last is to be contrasted with Europe, where the river names, even after over 3000 years of exclusive Indo-European presence, still bear evidence of their non-Indo-European and pre-Indo-European origins].

viii) In short, as per the linguistic consensus, the Indo-Europeans in 3000 BCE were still in and around their Original Homeland, and as per the Textual Analysis of the Rigveda, the Vedic Indo-Aryans around 3000 BCE were long-established residents of a purely Indo-European area in northern India: i.e. the Original Homeland was in northern India.

6. The Linguistic case is equally clear:

a. The only thing the Linguistic evidence shows is as detailed above: the existence of the Indo-European language family as a language family distinct from other language families; the inevitable proposition that all these present-day Indo-European languages originated from a common ancestral language (unfortunately not recorded anywhere, but approximately reconstructable) which may be called "Proto-Indo-European", and which was spoken in a restricted area which represented the Original Homeland of these languages.

However, the Linguistic evidence does not in any way show us that this Original Homeland was located in South Russia, or that it was located in any area other than India or that it was notlocated in India. The reconstructed PIE (Proto-Indo-European) language is very different from Vedic Sanskrit, but it is also very different from every other known ancient and present-day IE (Indo-European) language: the obvious logic is that languages are constantly changing: one cannot decide which house a far ancestor was living in by examining which of his many descendants (living in different houses) looks exactly, or most closely, like him. This fact is inadvertently admitted by a very prominent AIT-propagating western linguist, Hans H. Hock, who concedes that: "The claim that the āryas are indigenous to India can therefore be reconciled with the relationship of Indo-Aryan to the rest of Indo-European only under one of two hypotheses: Either the other Indo-European languages are descended from the earliest Indo-Aryan, identical or at least close to Vedic Sanskrit, or Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the ancestor of all the Indo-European languages, was spoken in India and (the speakers of) all the Indo-European languages other than Sanskrit/Indo-Aryan migrated out of India. For convenience, let us call the first alternative the ‘Sanskrit-origin’ hypothesis, and the second one, the ‘PIE-in-India’ hypothesis" (HOCK 1999a:1). And he further accepts the fact that the first version is easily refutable on linguistic grounds, but that the second one is not:"….the ‘Sanskrit-origin’ hypothesis runs into insurmountable difficulties [….but….] the likelihood of the ‘PIE-in-India’ hypothesis cannot be assessed on the basis of simIḷar robust evidence" (HOCK 1999a:2). "The ‘PIE-in-India’ hypothesis is not as easily refuted as the ‘Sanskrit-origin’ hypothesis", he admits, since it is neither proved nor disproved by the "‘hard-core’ linguistic evidence, such as sound changes, which can be subjected to critical and definitive analysis. Its cogency can be assessed only in terms of circumstantial arguments, especially arguments based on plausibility and simplicity" (HOCK 1999a:12). In short: the "PIE-in-India" hypothesis cannot be refuted on the basis of linguistic evidence, but only on a logical understanding of the linguistic facts.

And while every single linguistic fact cited by the Indologists to prove the AIT or to dismiss theIndian Homeland hypothesis can be shown to prove exactly the opposite, there is plenty of linguistic evidence - determinedly ignored by the Indologists - which cannot be explained by any other hypothesis than an Indian Homeland hypothesis. To give just a few examples: the common word for elephant/ivory in many IE branches (Sanskrit ibha, Latin ebur, Greek el-ephas, Hittite lahpa) with India being the only IE area having elephants; the branches to the east of the Semitic line (Iranian, Indo-Aryan and Tocharian) not having many important words borrowed from Semitic (e.g. wine, taurus, etc.) found in all the other branches to the west (indicating an IE movement from east to west across the Semitic longitudes); common words from eastern Siberia found in the Germanic and Celtic branches the one hand and the Chinese,Yeneseian and Altaic languages (indicating that the Germanic and Celtic branches passed from the areas to the north of Central Asia); the large-scale one-way borrowings from Indo-Aryanand Iranian languages into the Uralic languages of eastern Europe with no borrowings in the opposite direction (again indicating a migration of small groups of Indo-Aryan and Iranian language speakers from the east to the west across Central Asia and Eurasia); the presence of "pre-Indo-Iranian" linguistic features (such as a distinction between r and l) in Indo-Aryanlanguages in the eastern parts of northern India; primitive connections between the proto-Austronesian and PIE languages, etc., etc. On the other hand, not a single linguistic fact militates against the Out-of-India Theory (OIT) or Indian Homeland Theory.

Therefore, all the three sciences associated with the "Aryan" question, Archaeology, Textual Analysis and Linguistics, prove the AIT wrong and the OIT right. In desperation, supporters of the AIT (both Leftist and other anti-Hindu elements as well as staunch but racist-casteist Hindus like Manasataramgini and Kalavai Venkat and their fans and followers) are today abandoning these three sciences and latching on to extremely dubious and fake pop-"Genetic" arguments to fight their ideological battles. They have now been joined by ideologically motivated film-makers.

II. True Aryan History.

The true history of Aryan culture and civilization is recorded in the traditional historical narrative of India recorded primarily in the Puranas, and it can be elucidated by the Textual Analysis of the oldest recorded Indian text, the Rigveda. We have an advantage over traditional Indian analysts of the Vedic texts, since we have before us the evidence uncovered by the study of modern Linguistics which helps us to unravel this true history, whose geographical reach extends far beyond the geography and period of the Rigveda.

The Puranas contain masses and masses of mythical "data", but here we are only concerned with what they tell us about Manu Vaivasvata and his ten sons. Nine sons were Ikṣvāku, Nābhāga, Dhṛiṣṭa, Śaryāti, Nariṣyanta, Prāṁśu, Ṛṣṭa, Karuṣa and Pṛṣadhra, and there was one daughter named Iḷaa: the daughter Iḷaa (as per a mythical story narrated in the Puranas) became a man named Iḷa or Sudyumna, or (as per another mythical story) Sudyumna was an original son of Manu who was converted (due to a spell) into a woman named Iḷaa, and was later reconverted back into a man named Iḷa. According to tradition, Manu Vaivasvata ruled over the whole of India, and the land was divided between his ten sons. However, for all practical purposes (and ignoring the mythical chaff), the Puranas, whose detailed narrative is restricted primarily to the Indian area to the north of the Vindhyas, concentrate only on the history of the descendants of two sons: Ikṣvāku and Iḷa. The descendants of Ikṣvāku are said to belong to the Solar Race, and the descendants of Iḷa are said to belong to the Lunar Race. The history of the descendants of the other eight sons of Manu is either totally missing, or they are perfunctorily mentioned in confused myths in between narratives involving the Aikṣvākus and the Aiḷas.

The historical data we get from amidst all the myths is the following:

1. The tribes described as descended from Ikṣvāku lived in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The descendants of Iḷa were divided into five main conglomerates of tribes (mythically treated in the later narratives as descended from the five sons of Yayāti, a descendant of Iḷa): the Pūrutribes in the general Area of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, the Anu tribes to their North in the areas of Kashmir and the areas to its immediate west, the Druhyu tribes to the West in the areas of the Greater Punjab, the Yadu tribes to the Southwest in the areas of Gujarat, Rajasthan and western Madhya Pradesh, and the Turvasu tribes to the Southeast (to the east of the Yadutribes).

The Puranas, just as they fail to give details of the history and even the precise geography of the other eight sons of Manu, fail to give details of the history and even the precise geography of the Turvasu tribes (who are generally mentioned in tandem with the more important Yadu tribes). The main concentration of Puranic (and the Epic and other later traditional) narrative is on the history of the Pūru tribes of the western north, the Ikṣvāku tribes of the eastern north, and the Yadu tribes of the southwestern north. The early history of the Druhyu tribes is given, but later they disappear from the horizon (for reasons that we will see presently) and the history of the Anu tribes occupies a comparatively peripheral space in the Puranas (again for obvious reasons, as we will see).

2. Manu is regarded as the traditional ancestor of all the people of India. While we get details of the geography and history only of the descendants of Ikṣvāku and Iḷa, the clear implication is that all the people of the different parts of India are descended from Manu, including the people in the areas to the south of the Vindhyas and the areas to the east of Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, who are regarded as descendants of the other eight sons of Manu.

The details of the geography and history of the people from the other parts of India (including perhaps the areas of the descendants of Turvasu) are missing from the earlier narrative because, due to distance from the main centre of Puranic compIḷation in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, there was less direct and regular interaction with them or the details of their activities were less detailedly known to the originally Pūru compilers of the Vedic and Puranic texts. The Pūru tribes were originally mainly concerned with their own history and traditions (and to a secondary extent that of the Ikṣvāku tribes to their east and the Yadu tribes to their south), and they had also developed extremely complicated techniques of maintaining oral traditions, unparalleled anywhere else in the world, which allowed them, for example, to keep their Vedic hymns orally alive for thousands of years without the change of a word or syllable or even tone.

The Aryan history we get from the records is of two kinds:

1. Indian or "Hindu" history.

2. International or "Indo-European" history.

1. Indian or "Hindu" history: Recorded Indian history starts with the Rigveda, the book of the Pūru tribal conglomerate - in fact the book originally of one sub-tribe among the Pūru: the Bharata sub-tribe. This being the oldest maintained record in India (and definitely also one of the oldest, if not the oldest, coherent record in the world), it starts with the religion, culture and history of the Bharata Pūru tribe inhabiting mainly Haryana and westernmost Uttar Pradesh. [The Puranas also record the core of the history of northern India. But, being completely swamped by mythological and religious data, and, not maintained with the same rigidity as the Vedic texts and therefore being full of alterations, modifications and later data, they must be used only in order to supplement and corroborate the evidence of the Rigveda].

The Rigveda records the expansion of the Bharata Pūru tribe westwards into the Greater Punjab region then inhabited mainly by the Anu tribes. The subsequent Vedic Samhitas and post-Samhita Vedic texts, as well as the Puranic accounts, show the expansion of the Vedic culture of the Pūru tribes inwards into the areas of the Ikṣvāku tribes in the east and the Yadutribes to the south, and subsequently all over northern India, and then all over India. In the process, this gave birth to the glorious pan-Indian Hindu religion and culture (or Parliament of religions and cultures) which incorporated into itself the religious and cultural elements of the different non-Pūru tribes in different parts of the country, and made the Gods, sacred places and sacred rivers of every tribe in every part of the country equally sacred to the members of every other tribe in every other part of the country, and united the whole land into one broad and complex religio-cultural unit. The point is that in this Hindu culture, the original religious elements of the Pūru tribes (the Vedic hymns and different types of Vedic yajnas) became just one nominal part of the whole religion, subordinated in actual importance to the elements from the other tribes: the philosophical concepts (Upanishads, Buddhism, Jainism, Charvaka's philosophies, etc.) from the Ikṣvāku tribes, tantrism from tribes further east, idol-worship and temple culture from the tribes in South India, etc. Except for the fact that this religious journey commenced with the Indo-European Vedic language of the Pūru tribes (in which the Rigveda was composed, and which therefore made Sanskrit as a whole the sacred language of Hinduism), there is nothing particularly Pūru or even Indo-European in Hinduism: in fact the religio-cultural elements of the non-Pūru Indo-European tribes of northern India, and the Austric and Dravidian language speaking tribes, today constitute almost the whole body of Hinduism, which, in a sense, is truly a grand Parliament of the religions of all the descendants of the mythical sons of the mythical Manu.

2. International or "Indo-European" history: While the history of the Pūru tribes in interaction with the other tribes in the interior of India to their east and south produced Hindu or Indian culture and civilization; the history of the Pūru tribes in interaction with the Anu and Druhyutribes to their north, west and northwest, set in motion two chains of events which, in the course of time, led to the migrations of the Indo-European languages in pre-historic times from India to Iran and Central Asia, West Asia and Europe. With the spread of European Imperialism and colonialism in the last few centuries, today these Indo-European languages are the predominant languages in four of the six inhabited continents of the world (i.e. in Europe, North America, South America, and Australia), the dominant languages in large parts of a fifth continent (Asia), and at least politically and administratively the most important force in the sixth (Africa).

As per the accepted linguistic consensus, the first two IE dialects to move out from the Homeland (wherever that Homeland is to be situated) were the speakers of the proto-Anatolian(proto-Hittite) and the proto-Tocharian dialect in that order. Then the speakers of the five European ancestral dialects, proto-Italic, proto-Celtic, proto-Germanic, proto-Baltic and proto-Slavic. The five dialects to remain in the Homeland for a period after that, and to develop many new linguistic features in common, were the speakers of the proto-Albanian, proto-Greek, proto-Armenian, proto-Iranian and proto-Indo-Aryan dialects. There is no consensus about the exact order of migration of these last five dialects, but the logical implication of this should be that the Homeland was located in the historical area of one of these five branches, which continued to remain in the Homeland after the migration of the other four. All the twelve dialects, however, remained in contiguous areas inside and just outside the Homeland in various degrees of contact with each other till around 3000 BCE, after which they started decisively breaking away from each other and moving (in the course of time) into their earliest known historical habitats.

As per recorded history in the Indian texts, there were two distinct waves of Indo-European migrations: a Druhyu migration and an Anu migration.

The Druhyu migrations:

The Puranas record that the Druhyu tribes were originally inhabitants of the Greater Punjab area to the west of the Pūru tribes.

Historical conflicts between the Druhyu tribes on the one hand and all the other tribes to their east and northeast led to major conflicts which resulted in their being driven out from the Greater Punjab into Afghanistan, and their space in the Greater Punjab being occupied by the Anu tribes.

All the scholars who have translated or studied the traditional historical literature have noted the significance of the Puranic traditions which relate that, several generations later (i.e. gradually, in the course of time), the Druhyu slowly migrated to the north from this area (i.e. from Afghanistan), and established settlements in the northern areas:

"Indian tradition distinctly asserts that there was an AIḷa outflow of the Druhyus through the northwest into the countries beyond, where they founded various kingdoms" (PARGITER 1962:298).

"Five Purāṇas add that Pracetas’ descendants spread out into the mleccha countries to the north beyond India and founded kingdoms there" (BHARGAVA 1956/1971:99).

"After a time, being overpopulated, the Druhyus crossed the borders of India and founded many principalities in the Mleccha territories in the north, and probably carried the Aryan culture beyond the frontiers of India" (MAJUMDAR 1951/1996:283).

The Early Druhyus: The first group among the Druhyu to migrate northwards and settle down in Central Asia were the speakers of the proto-Anatolian (or proto-Hittite) dialect. They settled down for a long period in the western part of Central Asia. The second group to move northwards were the speakers of the proto-Tocharian dialect, who settled down in the eastern part of Central Asia. This scenario is proved by many factors:

a. The above situation most naturally explains the logistics of the earliest recorded historical presence of these two branches:

Proto-Anatolian (proto-Hittite), after the movement from Afghanistan into western Central Asia, lands up near the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea. A natural expansion along the shores of the Caspian Sea would naturally lead to the northeastern borders of Anatolia; and it is from the northeastern borders of Anatolia that the Hittites made their entry into their earliest attested areas in West Asia.

Proto-Tocharian, in any case, lands almost directly into its earliest historically attested area after it moves out northwards from Afghanistan into Central Asia. This area, eastwards, is the very area attested by the archaeological discoveries of Tocharian documents and by all the suggested literary references to the Tocharian people in other ancient texts.

b. The Puranas refer to two great tribes or peoples living to the north of the Himalayas, whom they call the Uttara-Madra and the Uttara-Kuru. The Uttara-Kuru are easily identified with theTocharians: this is supported by the simIḷarity of the name Uttara-Kuru with the nameTocharian (Twghry in an Uighur text, and Tou-ch’u-lo or Tu-huo-lo in ancient Chinese Buddhist texts) suggesting that Uttara-Kuru may be a Sanskritization of the native appellation of the Tocharians, preserving, as closely as possible, what Henning calls "the consonantal skeleton (dental + velar + r) and the old u-sonant [which] appears in every specimen of the name" (HENNING 1978:225). Since the eastern of the two great tribes to the north were called theUttara-Kuru, the western must have been called the Uttara-Madra on the analogy of the actualKuru and the Madra tribes to the south being to the east and the west respectively; and the termUttara-Madra must therefore refer to the proto-Anatolians (proto-Hittites).

c. That the proto-Hittites may have had some contact with the Indo-Aryans well into the Vedic period, and that too in the Central Asian region itself, is suggested by the presence, in Hittite mythology, of Indra, who is so completely unknown to all the other Indo-European mythologies and traditions (except of course, the Avesta, where he has been demonized) that Lubotsky and Witzel (see WITZEL 2006:95) feel emboldened to classify it as a word borrowed by "Indo-Iranian" from a hypothetical BMAC language in Northern-Afghanistan/Central-Asia.

d. Finally, incredible as it may seem, we actually have some kind of racial evidence (though nothing to do with any "Aryan race") indicating that the proto-Hittites immigrated into West Asia from the east (Central Asia) rather than from the West: while the existence of the Hittites as a prominent historical tribe in West Asia has been known on the basis of detailed historical records since early times (they are very prominent in the Old Testament of the Bible), it was only in the beginning of the twentieth century that their language was discovered and studied in detail and they were conclusively identified linguistically as Indo-Europeans. Shortly after this, a paper in the Journal of the American Oriental Society makes the following incidental observations: "While the reading of the inscriptions by Hrozny and other scholars has almost conclusively shown that they spoke an Indo-European language, their physical type is clearly Mongoloid, as is shown by their representations both on their own sculptures and on Egyptian monuments. They had high cheek-bones and retreating foreheads." (CARNOY 1919:117).

The Later Druhyus: The other Druhyu groups later migrated northwards into Central Asia in the order indicated by the linguistic analysis, as well as by the linguistic connections of their dialects with each other: proto-Italic, proto-Celtic, proto-Germanic, proto-Baltic, proto-Slavic. After a long stay in Central Asia, and some interactions (resulting in different common features developed between individual groups) with the proto-Hittites and proto-Tocharians already in Central Asia, these five branches, linguistically referred to as the "European" or "northwestern" branches (which share a large vocabulary developed in common and missing in the other branches), slowly expanded and migrated in stages northwestwards across the expanse of Eurasia, and entered Europe from the east and spread out into different parts of Europe. This scenario is proved by many factors:

a. There are common linguistic features developed by individual European branches in common with proto-Hittite and proto-Tocharian: in the OIT, this is easily explained by the fact that they passed through the area (Central Asia) already inhabited by these two Early dialects. In the South Russian Steppe theory, there is no logical explanation: all the branches spread out in different directions like the rays of the sun, and while the proto-Hittite and proto-Tochariandialects moved southwards and eastwards respectively, the European branches moved out westwards from the alleged Steppe Homeland and there was no logical chance of individual interactions with the two Early dialects.

b. The only European group which preserves the original PIE priestly class (the Celtic group, whose religion exhibits the same two central religious features found in the Vedic and Avestan religions, i.e. hymnology and fire-worship) also preserves the original name Drui (gen. Druid): an analysis of the Vedic and Avestan evidence (details in my books) shows that the three conglomerates of northern tribes, the Pūru, Anu and Druhyu, had three distinct (but religiously simIḷar) priestly classes: the Angiras, Bhrgu/Atharvan and Druhyu (this third conglomerate of tribes, being more distant, was referred to in the Pūru texts by the name of their priestly class) respectively.

c. A very detailed and complex linguistic study by Johanna Nichols and a team of linguists, appropriately entitled "The Epicentre of the Indo-European Linguistic Spread", examines ancient loan-words from West Asia (Semitic and Sumerian) found in Indo-European and also in other language families like Caucasian (with three separate groups Kartvelian, Abkhaz-Circassian and Nakh-Daghestanian), and the mode and form of transmission of these loan-words into the Indo-European family as a whole as well as into particular branches, and combines this with the evidence of the spread of Uralic and its connections with Indo-European, and withseveral kinds of other linguistic evidence : "Several kinds of evidence for the PIE locus have been presented here. Ancient loanwords point to a locus along the desert trajectory, not particularly close to Mesopotamia and probably far out in the eastern hinterlands. The structure of the family tree, the accumulation of genetic diversity at the western periphery of the range, the location of Tocharian and its implications for early dialect geography, the early attestation of Anatolian in Asia Minor, and the geography of the centum-satem split all point in the same direction [….]: the long-standing westward trajectories of languages point to an eastward locus, and the spread of IE along all three trajectories points to a locus well to the east of the Caspian Sea. The satem shift also spread from a locus to the south-east of the Caspian, with satem languages showing up as later entrants along all three trajectory terminals. (The satem shift is a post-PIE but very early IE development).The locus of the IE spread was therefore somewhere in the vicinity of ancient Bactria-Sogdiana." (NICHOLS 1997:137): i.e. in the very area outside the exit point from Afghanistan into Central Asia indicated by the data in the Puranas regarding the emigration of the Druhyutribes.

d. Independently of the diverse linguistic evidence analyzed by Nichols above (which pertains to linguistic contacts of the European dialects with languages to the west and southwest of Central Asia), there is other linguistic evidence further east: A western academic scholar of Chinese origin, Tsung-tung Chang, shows, on the basis of a study of the relationship between the vocabulary of Old Chinese (as reconstructed by Bernard Karlgren, Grammata Serica, 1940, etc.) and the etymological roots of Proto-Indo-European vocabulary (as reconstructed by Julius Pokorny, Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, 1959) that there was a very strong Indo-European influence on the formative vocabulary of Old Chinese. His conclusions: "Among Indo-European dialects, Germanic languages seem to have been mostly akin to Old Chinese" (CHANG 1988:32), and all this indicates that "Indo-Europeans had coexisted for thousands of years in Central Asia [….] (before) they emigrated into Europe" (CHANG 1988:33).

The presence of proto-Germanic, as well as proto-Celtic, in ancient Central Asia is confirmed by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov as well, who deal with this point at length in section 12.7 in their book, entitled "The separation of the Ancient European dialects from Proto-Indo-European and the migration of Indo-European tribes across Central Asia" (GAMKRELIDZE 1995:831-847), where they trace the movement of the European Dialects from Central Asia to Europe on the basis of a trail of linguistic contacts between the European Dialects and various other language families on the route. This evidence includes (apart from borrowings from the European Dialects into Old Chinese, already discussed above) borrowings from the Yeneseian and Altaic languages into the European Dialects and vice versa.

e. Of all the extant Indo-European groups, it is the European Dialects for whom we have the clearest archaeological evidence regarding their movement into their historical habitats (i.e. most of Europe). As Winn points out: "A ‘common European horizon’ developed after 3000 BC, at about the time of the Pit Grave expansion (Kurgan Wave #3). Because of the particular style of ceramics produced, it is usually known as the Corded Ware Horizon. [….] The expansion of the Corded Ware cultural variants throughout central, eastern and northern Europe has been construed as the most likely scenario for the origin of PIE (Proto-Indo-European) language and culture. [….] the territory inhabited by the Corded ware/Battle Axe culture, after its expansions, geographically qualifies it to be the ancestor of the Western or European language branches: Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Celtic and Italic" (WINN 1995:343, 349-350). This archaeological evidence "does not [….] explain the presence of Indo-Europeans in Asia, Greece and Anatolia" (WINN 1995:343), but it explains the presence of the European branches, and their expansion through Eastern Europe to the northern and western parts of Europe.

The Anu migrations:

As already pointed out above, historical conflicts between the Druhyu tribes on the one hand and all the other tribes to their east and northeast led to major conflicts which resulted in their being driven out from the Greater Punjab into Afghanistan, and their space in the Greater Punjab being occupied by the Anu tribes. Now, the Anu tribes came to occupy two areas: the original areas in the North (in the areas of Kashmir and the areas to its immediate west), and the new areas to the South (originally occupied by the Druhyu tribes: the areas of the Greater Punjab). The original areas are still the areas of the proto-Iranian tribes: the speakers of the Pishacha or Nuristanilanguages. The Anu tribes consisted of the speakers of the four last remaining dialects of PIE (other than the Indo-Aryan tribes, who were Pūru), and the historical events, which led to their migration westwards by a different (in relation to the Druhyu migrations) southern route, are described in unmistakable detail in the Rigveda. The basic details are as follows (for greater details see my books or my following blog "The Recorded History of the Indo-European Migrations - Part 3 of 4 The Anu Migrations"):

a. As per the accepted linguistic consensus, the five IE groups to remain in the Homeland after the departure of the other seven, and to develop many new linguistic features in common, were the speakers of the proto-Albanian, proto-Greek, proto-Armenian, proto-Iranian and proto-Indo-Aryan dialects. The great historical incident recorded in the Rigveda is the dāśarājña battle, or "the Battle of the Ten Kings", and the two hymns which mainly describe this battle provide us the names of the different Anu tribes who united to fight against the expansionism of Sudās and the Bharata-s (i.e. the Vedic Indo-Aryan speakers): VII.18.5 Śimyu, VII.18.6 Bhṛgu, VII.18.7 Paktha, Bhalāna, Alina, Śiva, Viṣāṇin, VII.83.1 Parśu/Parśava, Pṛthu/Pārthava, Dāsa. Another major Anu tribe in the Puranas, and still present in the Punjab in later historical times, are the Madra. Incredibly, these names cover, in an almost continuous geographical belt, the names of historical Iranian, Armenian, Greek and Albanian tribes who cover in later historical times the entire sweep of areas extending westwards from the Punjab (the battleground of the dāśarājña battle) right up to southern and eastern Europe:

i) IRANIAN: Avestan Afghanistan: Sairima (Śimyu), Dahi (Dāsa); NE Afghanistan: Nuristani/Piśācin (Viṣāṇin); Pakhtoonistan (NW Pakistan), South Afghanistan: Pakhtoon/Pashtu (Paktha); Baluchistan (SW Pakistan), SE Iran: Bolan/Baluchi (Bhalāna); NE Iran: Parthian/Parthava (Pṛthu/Pārthava); SW Iran: Parsua/Persian (Parśu/Parśava); NW Iran: Madai/Median (Madra); Uzbekistan: Khiva/Khwarezmian (Śiva); W. Turkmenistan: Dahae(Dāsa); Ukraine, S, Russia: Alan (Alina), Sarmatian (Śimyu).

ii) ARMENIAN: Turkey: Phryge/Phrygian (Bhṛgu); Romania, Bulgaria: Dacian (Dāsa).

iii) GREEK: Greece:Hellene (Alina).

iv) ALBANIAN: Albania: Sirmio (Śimyu).

Their exodus is referred to in two other hymns in Book 7: VII.5.3 and VII.6.3.

The above mentioned tribes include the ancestors of other well-known ancient or modern Iranian tribes, including the Scythians (Sakas), Ossetes and Kurds, and even the presently Slavic-language speaking Serbs and Croats! The reader can check up the relevant encyclopedias (including Wikipedia) for the historical importance and geographical locations of all these different groups.

In short, the entire history of the Indo-European tribes in their Homeland in India, and their migration from India, is recorded in the Textual data in the Puranas and Rigveda, and corroborated by the Linguistic and Archaeological evidence. On the other hand, the AIT is a PURE LIE totally unsupported by Textual data, Linguistics or Archaeology.

It is time people understood the difference between the fake fabricated story of the "Aryan" Invasion of India, and the true History of the mythical sons of Manu (call them "Aryans" if you please, but it cannot be in the linguistic sense of "speakers of IE languages"), who include the speakers of all native Indian languages and the followers of all native Indian religions.

No-one should be allowed to brainwash divisive lies into the minds of the common Indian, fabricating hate-inspired and hate-instigating fictional stories of fake conflicts in ancient times between so-called "Aryans" and "Dravidians": whether Leftist and "Secularist" politicians, racist-casteist people (Hindu or anti-Hindu), "scholars" and writers, or the makers of films and serials.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

BHARGAVA 1956/1971: India in the Vedic Age: A History of Aryan Expansion in India. Purushottam Lal Bhargava. Upper India Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. Lucknow, 1956.

CARNOY 1919: Pre-Aryan Origins of the Persian Perfect. pp. 117-121 in The Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol.39, 1919.

CHANG 1988: Indo-European Vocabulary in Old Chinese: A New Thesis on the emergence of Chinese Language and Civilization in the Late Neolithic age. Chang, Tsung-tung. Sino-Platonic Papers Number 7, January 1988. Department of Oriental Studies, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1988.

ERDOSY 1989: Ethnicity in the Rigveda and its Bearing on the Question of Indo-European Origins. Erdosy, George. pp. 35-47 in “South Asian Studies” vol. 5. London.

ERDOSY 1995: Preface to “The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: language, material Culture and Ethnicity”, edited George Erdosy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin-NY, 1995.

GAMKRELIDZE 1995: Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and a Proto-Culture. Gamkrelidze, Thomas V. and Ivanov, V.V. Mouton de Gruyter, 1995, Berlin, New York.

HENNING 1978: The First Indo-Europeans in History. Henning, W.B., pp.215-230 in “Society and History ― Lectures in Honour of Karl August Wittfogel”, edited G. L. Ulmen, Mouton Publishers, The Hague-Paris-New York, 1978.

HOCK 1999a: Out of India? The linguistic evidence. Hock, Hans H. pp.1-18, in “Aryan and non-Aryan in South Asia: evidence, interpretation, and ideology” (proceedings of the International Seminar on Aryan and non-Aryan in South Asia, Univ. of Michigan, October 1996).

MAJUMDAR ed.1951/1996: The Vedic Age. General Editor Majumdar R.C. The History and Culture of the Indian People. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. Mumbai, 1951.

NICHOLS 1997: The Epicentre of the Indo-European Linguistic Spread. Nichols, Johanna. Chapter 8, in “Archaeology and Language, Vol. I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations”, ed. Roger Blench & Matthew Spriggs, Routledge, London and New York, 1997.

PARGITER 1962: Ancient Indian Historical Tradition. Pargiter F.E. Motilal Banarsidas, Delhi-Varanasi-Patna, 1962.

WINN 1995: Heaven, Heroes and Happiness: The Indo-European Roots of Western Ideology. Winn, Shan M.M. University Press of America, Lanham-New York-London, 1995.

WITZEL 2000a: The Languages of Harappa. Witzel, Michael. Feb. 17, 2000.

WITZEL 2005: Indocentrism: autochthonous visions of ancient India. Witzel, Michael.pp.341-404, in “The Indo-Aryan Controversy — Evidence and Inference in Indian history”, ed.Edwin F. Bryant and Laurie L. Patton, Routledge, London & New York, 2005.

Disputation poems are texts that feature discussion between two usually inarticulate litigants, such as trees, animals, seasons, or concepts. Poems of this type appear in a great many different cultures, the majority of which lived around the area of modern Iraq. The genre spans third millennium BCE Sumerian to contemporary Arabic poetry, through Jewish Aramaic, Parthian, Syriac, Classical Arabic, Persian, and Turkish literature. The topics often reflect the concerns of the time in which the poems were composed. Thus, 21

Disputation poems are texts that feature discussion between two usually inarticulate litigants, such as trees, animals, seasons, or concepts. Poems of this type appear in a great many different cultures, the majority of which lived around the area of modern Iraq. The genre spans third millennium BCE Sumerian to contemporary Arabic poetry, through Jewish Aramaic, Parthian, Syriac, Classical Arabic, Persian, and Turkish literature. The topics often reflect the concerns of the time in which the poems were composed. Thus, 21

MINHAZ MERCHANT

MINHAZ MERCHANT

![[image]](http://archive.archaeology.org/0809/abstracts/thumbnails/letter1_300.gif)

![[image]](http://archive.archaeology.org/0809/abstracts/thumbnails/letter2_map.gif)

![[image]](http://archive.archaeology.org/0809/abstracts/thumbnails/letter3_stones.gif)

![[image]](http://archive.archaeology.org/0809/abstracts/thumbnails/letter4.gif)

Taurine-shaped bead

Taurine-shaped bead

Ruhuna coin

Ruhuna coin

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge  Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.

Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032 (with fish and arrow hieroglyph)

Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032 (with fish and arrow hieroglyph)

m1406 Mohenjo-daro seal. Hieroglyphs: thread of three stands

m1406 Mohenjo-daro seal. Hieroglyphs: thread of three stands  m1521A copper tablet. Harappa Script Corpora

m1521A copper tablet. Harappa Script Corpora

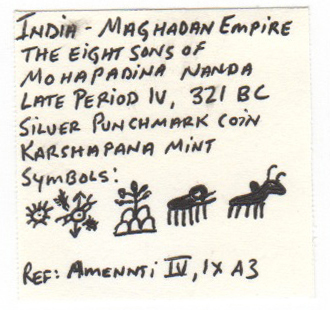

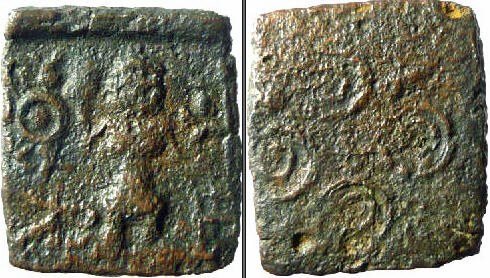

Sunga 185-75 BCE karabha'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Sunga 185-75 BCE karabha'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Kausambi 200 BCE

Kausambi 200 BCE kola 'tiger' rebus: kol'blacksmith' karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol'blacksmith' karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

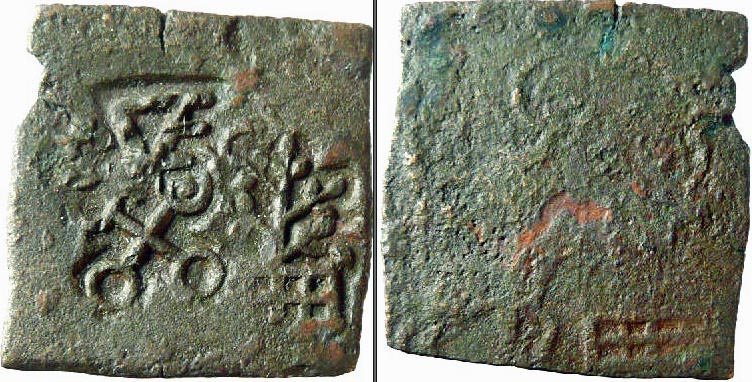

Taxila. Pushkalavati 185-160 BCE Karshapana

Taxila. Pushkalavati 185-160 BCE Karshapana Kalinga. Copper punch-marked 3rd cent. BCEarka 'sun' rebus: arka 'copper gold'

Kalinga. Copper punch-marked 3rd cent. BCEarka 'sun' rebus: arka 'copper gold'

Silver punch-marked

Silver punch-marked Asmaka

Asmaka

Vidarbha janapada

Vidarbha janapada

Silver 2.78 g

Silver 2.78 g

Eran-Vidisha AE 1/2 karshapana, Hastideva, four punch type

Eran-Vidisha AE 1/2 karshapana, Hastideva, four punch type

Chutus of Banavasi / Anandas of Karwar, Mulananda, 78-175 CE, Lead, 9.55g, Swastika to left of Tree-in-railing

Chutus of Banavasi / Anandas of Karwar, Mulananda, 78-175 CE, Lead, 9.55g, Swastika to left of Tree-in-railing Vidarbha, 200 BCE, Cast Copper, 3.86g, Swastika with Taurine symbol

Vidarbha, 200 BCE, Cast Copper, 3.86g, Swastika with Taurine symbol

Taxila, 300-100 BCE, Copper, 1.5 Karshapana, 21mm, 12.43g, Elephant / Lion

Taxila, 300-100 BCE, Copper, 1.5 Karshapana, 21mm, 12.43g, Elephant / Lion

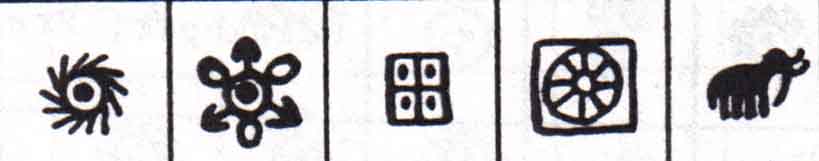

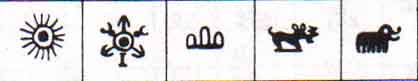

Magadha janapada. Dotted circle is connected by three allows. Oval hieroglyphs occur between the arrows. Sun hieroglyph is shown on the right top corner, clockwise next to a crucible hieroglyph and a circle with strand hieroglyph.

Magadha janapada. Dotted circle is connected by three allows. Oval hieroglyphs occur between the arrows. Sun hieroglyph is shown on the right top corner, clockwise next to a crucible hieroglyph and a circle with strand hieroglyph.

The coins fall into two main classes; (1) rectangular and (2) roughly circular or oval ; each of these again has a cross division into (a) thin and (b) thick. Though no clear line of separation exists, the thickness varying from that of thin cardboard to about 0.12 inch, the difference between the thin and wide coins, usually covered with punch marks, which are the earliest (

The coins fall into two main classes; (1) rectangular and (2) roughly circular or oval ; each of these again has a cross division into (a) thin and (b) thick. Though no clear line of separation exists, the thickness varying from that of thin cardboard to about 0.12 inch, the difference between the thin and wide coins, usually covered with punch marks, which are the earliest ( (

(

Pl. 7

Pl. 7 Pl. 8

Pl. 8 Pl. 9

Pl. 9 Pl. 10

Pl. 10 Pl. 11

Pl. 11 Pl. 12

Pl. 12 Pl. 13

Pl. 13 Pl. 14

Pl. 14 A similar coin, but roughly circular and lenticular, was found at the north end of Vessagiriya, Anuradapura its diameter is 0.53 inch, and weight 29.8 grains. Alleged similar pieces unearthed at Kantarodai in the Jaffna peninsular are described by Mr. P. E. Pieris in his paper on "Nagadipa",in J.R.A.S., C.8., Vol, XXVIII, No. 72 of 1919. Pl. XII, Nos. 18, 19,21,22,26, Most seem to be the cores of eldlings, but one (No, 18) is distinctly concave: its size is 0.62 by 0.43 inch, and its weight is 28.6 grains, At Tirukketisvaram was also found a flat rectangular piece with rounded corners. One side is apparently blank; on the other is what seems to be a fish with long projecting fins, with which design should be compared that of the silver coins described above. It weighs in its broken condition 29.2 grains, and measures 0.49 x 0.45 x 0.11 inch. From the same place come two circular coins, which may be noticed here. One is thick, flat on one side, the design on which is undecipherable, and convex and worn smooth on the other ; the second is, perhaps, blank on both sides. The diameter and weight are 0.57 and 0.33 inch, and 3l.2 and 6.2 grains, respectively.

A similar coin, but roughly circular and lenticular, was found at the north end of Vessagiriya, Anuradapura its diameter is 0.53 inch, and weight 29.8 grains. Alleged similar pieces unearthed at Kantarodai in the Jaffna peninsular are described by Mr. P. E. Pieris in his paper on "Nagadipa",in J.R.A.S., C.8., Vol, XXVIII, No. 72 of 1919. Pl. XII, Nos. 18, 19,21,22,26, Most seem to be the cores of eldlings, but one (No, 18) is distinctly concave: its size is 0.62 by 0.43 inch, and its weight is 28.6 grains, At Tirukketisvaram was also found a flat rectangular piece with rounded corners. One side is apparently blank; on the other is what seems to be a fish with long projecting fins, with which design should be compared that of the silver coins described above. It weighs in its broken condition 29.2 grains, and measures 0.49 x 0.45 x 0.11 inch. From the same place come two circular coins, which may be noticed here. One is thick, flat on one side, the design on which is undecipherable, and convex and worn smooth on the other ; the second is, perhaps, blank on both sides. The diameter and weight are 0.57 and 0.33 inch, and 3l.2 and 6.2 grains, respectively.![[Prev]](http://coins.lakdiva.org/codrington/greyleft.gif)

![[Next]](http://coins.lakdiva.org/codrington/greyright.gif)

ranku 'liquid measure' (Santali) Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Note: The same hieroglyph is deployed on one of two pure tin ingots discovered in a shipwreck in Haifa, Israel).

ranku 'liquid measure' (Santali) Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Note: The same hieroglyph is deployed on one of two pure tin ingots discovered in a shipwreck in Haifa, Israel).

Reply